Artificial languages. Why create artificial languages

Esperanto is the most widely spoken artificial language in the world. Now, according to various sources, from several hundred thousand to a million people speak it. It was invented by the Czech oculist Lazar (Ludwig) Markovich Zamenhof in 1887 and got its name from the pseudonym of the author (Lazar signed his name in the textbook as Esperanto - “hopeful”).

Like other artificial languages (more precisely, most of them) it has an easy-to-learn grammar. The alphabet has 28 letters (23 consonants, 5 vowels), and is based on Latin. Some enthusiasts have even nicknamed it “the Latin of the new millennium.”

Most Esperanto words are composed of Romance and Germanic roots: roots are borrowed from French, English, German and Italian languages. There are also many international words in the language that are understandable without translation. 29 words are borrowed from Russian, among them the word “borscht”.

Harry Harrison spoke Esperanto and actively promoted this language in his novels. Thus, in the “World of the Steel Rat” series, the inhabitants of the Galaxy speak mainly Esperanto. About 250 newspapers and magazines are published in Esperanto, and four radio stations broadcast.

Interlingua (occidental)

Appeared in 1922 in Europe thanks to the linguist Edgar de Wall. In many ways it is similar to Esperanto: it has many borrowings from Romano-Germanic languages and the same system of language construction as in them. The original name of the language - Occidental - became an obstacle to its spread after World War II. In the countries of the communist bloc it was believed that after the pro-Western language, anti-revolutionary ideas would creep in. Then Occidental began to be called Interlingua.

Volapyuk

In 1879, God appeared to the author of the language, priest Johann Martin Schleyer, in a dream and ordered him to invent and write down his own language, which Schleyer immediately began to do. All night he wrote down his grammar, the meanings of words, sentences, and then entire poems. The German language became the basis of Volapük; Schleyer boldly deformed the words of the English and French languages, reshaping them into new way. In Volapük, for some reason, he decided to abandon the [r] sound. More precisely, not even for some reason, but for a very specific one: it seemed to him that this sound would cause difficulties for the Chinese who decided to learn Volapuk.

At first, the language became quite popular due to its simplicity. It published 25 magazines, wrote 316 textbooks in 25 languages, and operated 283 clubs. For one person, Volapuk even became his native language - this is the daughter of Volapuk professor Henry Conn (unfortunately, nothing is known about her life).

Gradually, interest in the language began to decline, but in 1931 a group of Volapükists led by the scientist Ari de Jong carried out a reform of the language, and for some time its popularity increased again. But then the Nazis came to power and banned everything in Europe foreign languages. Today there are only two to three dozen people in the world who speak Volapuk. However, Wikipedia has a section written in Volapuk.

Loglan

Linguist John Cook coined log ical lan guage in 1955 as an alternative to conventional, non-ideal languages. And suddenly the language, which was created mostly for scientific research, found its fans. Of course! After all, it does not have such concepts as tense in verbs or number in nouns. It is assumed that this is already clear to the interlocutors from the context of the conversation. But the language has a lot of interjections, with the help of which it is supposed to express shades of emotions. There are about twenty of them, and they represent a spectrum of feelings from love to hate. And they sound like this: eew! (love), yay! (surprise), wow! (happiness), etc. There are also no commas or other punctuation marks. A miracle, not a language!

Developed by Ohio minister Edward Foster. Immediately after its appearance, the language became very popular: in the first years, even two newspapers were published, manuals and dictionaries were published. Foster was able to receive a grant from the International Auxiliary Language Association. Main feature language ro: words were built according to a categorical scheme. For example, red - bofoc, yellow - bofof, orange - bofod. The disadvantage of this system is that it is almost impossible to distinguish words by ear. This is probably why the language did not arouse much interest among the public.

Solresol

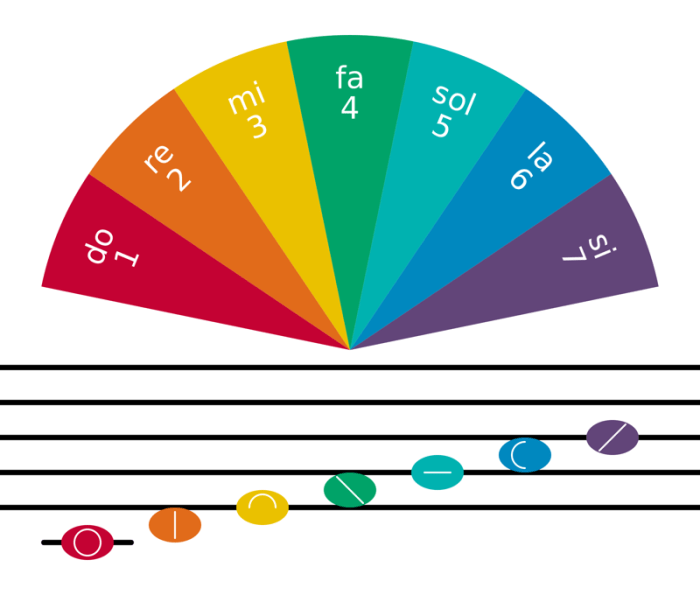

Appeared in 1817. The creator, Frenchman Jean Francois Sudre, believed that everything in the world can be explained with the help of notes. Language, in fact, consists of them. It has a total of 2660 words: 7 one-syllables, 49 two-syllables, 336 three-syllables and 2268 four-syllables. To denote opposite concepts, mirroring of the word is used: falla - good, lyafa - bad.

Solresol had several scripts. It was possible to communicate on it by writing down notes on a stave, the names of notes, the first seven digits of Arabic writing, the first letters of the Latin alphabet, special shorthand symbols and the colors of the rainbow. Accordingly, it was possible to communicate in Solresol not only by pronouncing words, but also by playing a musical instrument or singing, as well as in the language of the deaf and dumb.

The language has found a lot of fans, including among famous people. Famous followers of Solresol were, for example, Victor Hugo, Alexander Humboldt, Lamartine.

Ithkuil

A specially invented language to communicate on philosophical topics (however, this can be done with the same success in any other language, it will still be incomprehensible!). The creation of the language took its author John Quijada almost 30 years (from 1978 to 2004), and even then he believes that he is not yet finished with the vocabulary. By the way, there are 81 cases in ifkuil, and the meanings of words are conveyed using morphemes. Thus, a long thought can be conveyed very briefly. It's like you want to archive the words.

Tokipona

The simplest artificial language in the world was created in 2011 by Canadian linguist Sonia Helen Kisa (real name, however, Christopher Richard). The Tokipona dictionary has only 118 words (each with multiple meanings), and speakers are generally expected to understand what is being said from the context of the conversation itself. The creator of tokipona believes that he is closer to understanding the language of the future, which Tyler Durden spoke about in “Fight Club.”

Klingon

Linguist Marc Okrand invented Klingon for Paramount Pictures to be used by aliens in the Star Trek movie. They were, in fact, talking. But besides them, the language was adopted by numerous fans of the series, and currently there is an Institute of the Klingon Language in the USA, which publishes periodicals and translations of literary classics, there is Klingon-language rock music (for example, the band Stokovor performs its songs in the death metal genre exclusively in Klingon) , theatrical performances and even a section of the Google search engine.

Submitting your good work to the knowledge base is easy. Use the form below

Students, graduate students, young scientists who use the knowledge base in their studies and work will be very grateful to you.

Posted on http://www.allbest.ru/

Introduction

Constructed languages -- special languages, which, unlike natural ones, are designed purposefully. There are already more than a thousand such languages, and more and more are constantly being created.

The following types of artificial languages are distinguished:

· Programming languages and computer languages - languages for automatic processing of information using a computer.

Information languages - languages used in various systems information processing.

· Formalized languages of science - languages intended for symbolic recording scientific facts and theories of mathematics, logic, chemistry and other sciences.

· International auxiliary languages (planned) - languages created from elements natural languages and offered as an aid to international communication.

· Languages of non-existent peoples created for fictional or entertainment purposes, for example: the Elvish language, invented by J. Tolkien, the Klingon language, invented by Marc Okrand for the science fiction series “Star Trek” (see Fictional languages), the Navi language, created for the film “Avatar” "

The idea of creating a new language of international communication arose in the 17th-18th centuries as a result of the gradual decrease in the international role of Latin. Initially, these were predominantly projects of a rational language, freed from the logical errors of living languages and based on the logical classification of concepts. Later, projects based on models and materials from living languages appear. The first such project was the station wagon, published in 1868 in Paris by Jean Pirro. Pirro's project, which anticipated many details of later projects, went unnoticed by the public.

The next international language project was Volapük, created in 1880 by the German linguist I. Schleyer. It caused quite a stir in society.

According to the purpose of creation, artificial languages can be divided into the following groups:

· Philosophical and logical languages - languages that have a clear logical structure of word formation and syntax: Lojban, Tokipona, Ifkuil, Ilaksh.

· Auxiliary languages - intended for practical communication: Esperanto, Interlingua, Slovio, Slovyanski.

· Artistic or aesthetic languages - created for creative and aesthetic pleasure: Quenya.

· Language is also created to set up an experiment, for example, to test the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis (that the language a person speaks limits consciousness, drives it into a certain framework).

According to their structure, artificial language projects can be divided into the following groups:

· A priori languages - based on logical or empirical classifications of concepts: loglan, lojban, rho, solresol, ifkuil, ilaksh.

· A posteriori languages - languages built primarily on the basis of international vocabulary: Interlingua, Occidental

· Mixed languages-- words and word formation are partly borrowed from non-artificial languages, partly created on the basis of artificially invented words and word-formation elements: Volapuk, Ido, Esperanto, Neo.

The number of speakers of artificial languages can only be estimated approximately, due to the fact that there is no systematic record of speakers.

artificial language international alphabet

The Volapuk alphabet is based on Latin and consists of 27 characters. This language is distinguished by very simple phonetics, which should have made it easier to learn and pronounce for children and peoples whose language does not have complex combinations of consonants. The roots of most words in Volapük are borrowed from English and French, but modified to fit the rules of the new language. Volapük has 4 cases: nominative, genitive, dative, accusative; the stress always falls on the last syllable. The disadvantages of this language include a complex system of formation of verbs and various verb forms.

By 1889, 25 magazines in Volapuk were published all over the world and 316 textbooks were written in 25 languages, and the number of clubs for lovers of this language almost reached three hundred. However, gradually interest in this language began to fade away, and this process was especially strongly influenced by internal conflicts in the Volapuk Academy and the emergence of a new, simpler and more elegant planned language - Esperanto. It is believed that there are currently only about 20-30 people in the world who own Volapük.

Esperanto

The most famous and widespread artificial language was Esperanto (Ludwik Zamenhof, 1887) - the only artificial language that became widespread and united quite a lot of supporters of an international language. However, the more correct term is not “artificial”, but “planned”, that is, created specifically for international communication.

This language was constructed by the Warsaw physician and linguist Lazar (Ludwig) Markovich Zamenhof in 1887. He called his creation Internacia (international). The word "Esperanto" was originally the pseudonym under which Zamenhof published his works. Translated from the new language, it meant “hopeful.”

Esperanto is based on international words borrowed from Latin and Greek, and 16 grammatical rules with no exceptions.

This language has no grammatical gender, it has only two cases - nominative and accusative, and the meanings of the rest are conveyed using prepositions.

The alphabet is based on Latin, and all parts of speech have fixed endings: -o for nouns, -a for adjectives, -i for infinitive verbs, -e for derived adverbs.

All this makes Esperanto so in simple language that an unprepared person can learn to speak it quite fluently in a few months of regular practice. In order to learn any of the natural languages at the same level, it takes at least several years.

Currently, Esperanto is actively used, according to various estimates, from several tens of thousands to several million people. It is believed that for ~500-1000 people this language is their native language, that is, studied from the moment of birth. Usually these are children from marriages where the parents belong to different nations and use Esperanto for intra-family communication.

Esperanto has descendant languages that do not have a number of shortcomings that exist in Esperanto. The most famous among these languages are Esperantido and Novial. However, none of them will become as widespread as Esperanto.

Ido is a kind of descendant of Esperanto. It was created by the French Esperantist Louis de Beaufront, the French mathematician Louis Couture and the Danish linguist Otto Jespersen. Ido was proposed as an improved version of Esperanto. It is estimated that up to 5,000 people speak Ido today. At the time of its creation, about 10% of Esperantists switched to it, but the Ido language did not gain worldwide popularity.

Ido uses the Latin alphabet: it has only 26 letters, and there are no letters with dots, dashes or other umlauts.

The most significant changes in this "offspring" Esperanto originated in phonetics. Let us recall that Esperanto has 28 letters, using diacritics (just dots and dashes above letters), and Ido has only 26. The phoneme h was excluded from the language, and an optional pronunciation of the letter j appeared - j [?] (that is , now it’s not always the same as being heard and written, you already have to remember the sequences of letters with different sounds). These are the most significant differences, there are others.

The stress does not always fall on the penultimate syllable: for example, in infinitives the stress now falls on the last one.

The biggest changes occurred in word formation: in Esperanto, knowing the root, you only had to add to it the endings of the desired part of speech. In the Ido language, nouns are formed from verbs and from adjectives in different ways, so it is necessary to know whether we are forming a noun from the root of an adjective or a verb.

There are also a number of less significant differences.

Even though Ido did not become a popular language, he was able to enrich Esperanto with a number of affixes (suffixes and prefixes), some of which were transferred to Esperanto good words and expressions.

Loglan was developed specifically for linguistic research. It got its name from the English phrase “logical language”, which means “logical language”. Dr James Cook Brown began work on the new language in 1955, and the first paper on Loglan was published in 1960. The first meeting of people interested in Brown's brainchild took place in 1972; and three years later Brown's book, Loglan 1: A Logical Language, was published.

Brown's main goal was to create a language free from the contradictions and inaccuracies inherent in natural languages. He envisioned that Loglan could be used to test the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis of linguistic relativity, according to which the structure of language determines thinking and the way we experience reality, so much so that people who speak different languages, perceive the world differently and think differently.

The Loglan alphabet is based on the Latin script and consists of 28 letters. This language has only three parts of speech:

Nouns (names and titles) denoting specific individual objects;

Predicates that serve as most parts of speech and convey the meaning of statements;

Little words (English: “little words”) are pronouns, numerals and operators that express the speaker’s emotions and provide logical, grammatical, numerical and punctuation connections. There is no punctuation in the usual sense of the word in Loglan.

In 1965, Loglan was mentioned in R. Heinlein's story “The Moon Falls Hard” as a language used by a computer. The idea to make loglan human language, understandable by a computer, gained popularity, and in 1977-1982 work was done to finally rid it of contradictions and inaccuracies. As a result, after minor changes, Loglan became the world's first language with a grammar without logical conflicts.

In 1986, a split occurred among the Loglanists, which resulted in the creation of another artificial language - Lojban. Currently, interest in Loglan has noticeably decreased, but online communities still discuss language problems, and the Loglan Institute sends out its educational materials everyone who is interested in a new language. According to various sources, there are from several tens to several thousand people in the world who are able to understand texts in Loglan.

Toki Pona

Toki pona is a language created by Canadian linguist Sonya Helen Kisa and has become perhaps the simplest of artificial languages. The phrase “toki pona” can be translated as “good language” or “kind language.” It is believed that its creation was influenced by Chinese teaching Taoism and the works of primitivist philosophers. The first information about this language appeared in 2001.

The Toki Pona language includes only 120 roots, so almost all words in it have several meanings. The alphabet of this language consists of 14 letters: nine consonants (j k l m n p s t w) and five vowels (a e i o u). All official words are written in lowercase letters, only informal words, such as names of people or names of nations, begin with a capital letter. geographical places and religions. The spelling of words fully corresponds to their pronunciation; they are not modified by endings, prefixes or suffixes and can act as any part of speech. Sentences have a rigid structure. So, for example, the qualifying word always comes after the qualifying word (adjective after a noun; adverb after a verb, etc.) Toki Pona is primarily a language for communication on the Internet and serves as an example of Internet culture. It is believed that several hundred people currently use this language.

This language is the most famous of the languages created by the English linguist, philologist and writer J. R. R. Tolkien (1892-1973), who began his work in 1915 and continued it throughout his life. The development of Quenya, as well as the description of the Eldar, a people who could speak it, led to the creation of a classic literary work in the fantasy genre - the Lord of the Rings trilogy, as well as several other works published after the death of their author. Tolkien himself wrote about it this way: “No one believes me when I say that my long book is an attempt to create a world in which a language consistent with my personal aesthetics could be natural. However, it is true."

The basis for the creation of Quenya was Latin, as well as Finnish and Greek. Quenya is quite difficult to learn. It includes 10 cases: nominative, accusative, dative, genitive, instrumental, possessive, disjunctive, approximate, locative and corresponding. Quenya nouns are inflected in four numbers: singular, plural, fractional (used to indicate part of a group), and dual (used to indicate a pair of objects).

Tolkien also developed a special alphabet for Quenya, Tengwar, but the Latin alphabet is most often used for writing in this language. Currently, the number of people who speak this language to one degree or another reaches several tens of thousands. In Moscow alone there are at least 10 people who know it at a level sufficient to write poetry in it. Interest in Quenya increased significantly after the film adaptation of The Lord of the Rings. There are a number of textbooks on Quenya, as well as clubs for learning this language.

In the 20th century, another attempt was made to create a new artificial language. The project was called Slovio - the language of words. The main thing that distinguishes this language from all its artificial predecessors is its vocabulary, which is based on all existing languages of the Slavic group, the largest group of Indo-European languages. Moreover, the Slovio language is based on common Slavic vocabulary, which is understandable to all Slavs without exception.

Thus, Slovio is an artificial language created with the goal of being understandable to speakers of languages of the Slavic group without any additional study, and to facilitate learning as much as possible for non-speakers of Slavic languages. The creator of Slovio, linguist Mark Guchko, began working on it in 1999.

When creating Slovio, Mark Guchko used the experience gained during the creation and development of Esperanto. The difference between Slovio and Esperanto is that Esperanto was created on the basis of various European languages, and the vocabulary of Slovio consists of common Slavic words.

Slovio has 26 sounds, the main writing system is Latin without any diacritics, which can be read and written on any computer.

Slovio provides the ability to write in Cyrillic. Moreover, some sounds in different versions of the Cyrillic alphabet are indicated by different signs. Writing words in Cyrillic significantly simplifies the understanding of what is written by unprepared readers in Russia, Belarus, Ukraine, Bulgaria, Macedonia, Serbia and Montenegro, and the countries of the former USSR. But it should be remembered that not only will they not be able to read the Cyrillic alphabet, but sometimes they will not even be able to display it correctly in other countries and parts of the world. Cyrillic users will be able to read what is written in Latin alphabet, although with some inconvenience at first.

Slovio uses the most simplified grammar: there is no case declension, no grammatical genders. This is designed to make language learning easier and faster. Like natural Slavic languages, Slovio allows a free order of words in a sentence. Despite the simplified grammar, Slovio always accurately conveys the subject and object in a sentence, both in the direct order subject-predicate-object, and in the reverse order object-predicate-subject.

The main idea that the creators of Slovio developed is that the new language should be understandable without learning to all Slavs, who are the largest ethnic group in Europe. There are more than 400 million people in the world of Slavs. Therefore, Slovio is not just an artificial language for the sake of the idea itself, this language has great practical significance. It is believed that a German who has learned Slovio will be able to overcome language barrier in any of the Slavic countries, and learning Slovio is much easier than learning at least one of the Slavic languages.

Conclusion

Regardless of the reason for the creation of a particular artificial language, it is impossible for it to equivalently replace a natural language. It is deprived of a cultural and historical basis, its phonetics will always be conditional (there are examples when Esperantists from different countries had difficulty understanding each other due to the huge difference in the pronunciation of certain words), it does not have a sufficient number of speakers to be able to “ plunge" into their environment. Artificial languages, as a rule, are taught by fans of certain works of art in which these languages are used, programmers, mathematicians, linguists, or simply interested people. They can be considered as an instrument of interethnic communication, but only in a narrow circle of amateurs. Be that as it may, the idea of creating a universal language is still alive and well.

List of used literature

1. http://www.openlanguage.ru/iskusstvennye_jazyki

2. https://ru.wikipedia.org/wiki/Artificial_language

3. http://www.rae.ru/forum2012/274/1622

Posted on Allbest.ru

...Similar documents

The concept of "artificial language", a brief historical background on the formation and development of artificial languages. Typological classification and varieties of international artificial languages, their characteristics. Planned languages as a subject of interlinguistics.

abstract, added 06/30/2012

The formation of Romance languages during the collapse of the Roman Empire and the formation of barbarian states. Zones of distribution and major changes in the field of phonetics. The emergence of supra-dialectal literary languages. Modern classification of Romance languages.

abstract, added 05/16/2015

The concept of language classification. Genealogical, typological and areal classification. The largest families of languages in the world. Search for new types of classification. Indo-European family of languages. Families of languages of the peoples of Southeast Asia. The problem of extinction of world languages.

abstract, added 01/20/2016

Formation of national languages. Study of selected Germanic languages. General characteristics Germanic languages. Comparison of words of Germanic languages with words of other Indo-European languages. Features of the morphological system of ancient Germanic languages.

abstract, added 08/20/2011

Interaction of languages and patterns of their development. Tribal dialects and the formation of related languages. Formation of the Indo-European family of languages. Education of languages and nationalities. Education of nationalities and their languages in the past and at present.

course work, added 04/25/2006

The family tree of languages and how it is compiled. “Inserting” languages and “isolating” languages. Indo-European group of languages. Chukotka-Kamchatka and other languages Far East. Chinese language and its neighbors. Dravidian and other languages of continental Asia.

abstract, added 01/31/2011

Characteristics of interlinguistics – the science that studies artificial languages. Analysis of the principle of internationality, unambiguity, reversibility. Distinctive features of artificial languages: Occidental, Esperanto, Ido. Activities of interlinguistic organizations.

abstract, added 02/18/2010

Characteristics of the Baltic languages as a group of Indo-European languages. Modern area of their distribution and semantic features. Phonetics and morphology of the Lithuanian language. Specifics of the Latvian language. Dialects of the Prussian language. Features of Baltistics.

abstract, added 02/25/2012

Languages of the North and South America, Africa, Australia, Asia, Europe. What languages are there in the countries and how they differ. How languages influence each other. How languages appear and disappear. Classification of "dead" and "living" languages. Features of "world" languages.

abstract, added 01/09/2017

Constructed languages, their differences in specialization and purpose and determination of the degree of similarity to natural languages. Main types of artificial languages. The impossibility of using an artificial language in life is the main disadvantage of studying it.

Artificial languages are created for different purposes. Some are designed to give credibility to a fictional space in a book or film, others are designed to provide a new, simple and neutral means of communication, while others are constructed in order to comprehend and reflect the essence of the world. It is easy to get confused in the variety of artificial languages. But we can highlight a few of the most “unusual among the unusual.”

The maturity and longevity of each language also varies greatly. Some, such as Esperanto, have been “living” for several centuries, while others, having originated on Internet sites, exist through the efforts of their authors for a month or two.

For some artificial languages, sets of rules have been developed, while others consist of several dozen or hundreds of words designed to demonstrate the unusualness and dissimilarity of the language from others and do not form a coherent system.

Linkos: a language for communicating with aliens

The language "lincos" (lingua cosmica) was invented for contacts with extraterrestrial intelligence. It is impossible to speak it: there are no “sounds” as such. It is also impossible to write it down - it does not have graphic forms (“letters” in our understanding).

It is based on mathematical and logical principles. There are no synonyms or exceptions; only the most universal categories are used. Messages on Linkos must be transmitted using impulses different lengths, for example, light, radio signal, sound.

The inventor of linkos, Hans Freudenthal, proposed establishing contact by first transmitting the main signs - a period, “more” and “less”, “equal”. Next, the number system was explained. If the parties understood each other, then communication could be complicated. Linkos is the language of the initial stage of communication. If earthlings and aliens wanted to exchange poetry, they would have to invent a new language.

This is not a “ready-made” language, but a kind of framework - a set basic rules. It can be changed and improved depending on the task. Some principles of linkos were used to codify messages sent to solar-type stars.

Solresol: the most musical language

Even before the surge in popularity of artificial languages, the French musician Jean François Sudre came up with the Solresol language, based on combinations of seven notes. In total there are about twelve thousand words - from two-syllable to five-syllable. The part of speech was determined by the position of the stress.

You can write texts on Solresol using letters, notes or numbers, and you can draw them in seven colors. You can communicate on it using musical instruments(playing messages), flags (like Morse code) or just singing or talking. There are methods of communication in Solresol designed for the deaf and dumb.

The melody of this language can be illustrated by the example of the phrase “I love you”: in Solresol it would be “dore milyasi domi”. For brevity, it was proposed to omit the vowels in the letter - “dflr” means “kindness”, “frsm” - cat.

There is even a grammar Solresol, equipped with a dictionary. It has been translated into Russian.

Ithkuil: Experiencing the world through language

The “ifkuil” language is considered one of the most complex in terms of both grammar and writing. It refers to philosophical languages created for the most accurate and fast transmission of large amounts of information (the principle of “semantic compression”).

The creator of Ithkuil, John Quijada, did not set out to develop a language close to natural. His creation is based on the principles of logic, psychology and mathematics. Ithkuil is constantly improving: Quijada, up to this day, makes changes to the language he constructed.

Ithkuil is very complex in terms of grammar: it has 96 cases, and a small number of roots (about 3600) is compensated by a significant number of morphemes that clarify the meaning of the word. A small word in Ithkuil can only be translated into natural language using a long phrase.

It is proposed to write texts in Ifkuil using special characters - several thousand can be made from the combination of four basic characters. Each combination indicates both the pronunciation of the word and the morphological role of the element. You can write the text in any direction - from left to right, and from right to left, but the author himself suggests writing with a vertical “snake” and reading from the upper left corner.

At the same time, the Ithkuil alphabet was created on the basis of Latin. A simplified writing system is also built on the Latin alphabet, allowing you to type text on a computer.

In total, this artificial language has 13 vowel sounds and 45 consonants. Many of them are easy to pronounce individually, but in the text they form combinations that are difficult to pronounce. In addition, Ithkuil has a tone system, like, for example, Chinese.

In Ithkuil there are no jokes, no puns or ambiguity. The language system obliges us to add special morphemes to the roots that show exaggeration, understatement, and irony. This is almost perfect “legal” language - without ambiguity.

Tokipona: the simplest artificial language

A significant portion of artificial languages are created to be deliberately simplified so that they can be learned quickly and easily. The champion in simplicity is “tokipona” - it has 14 letters and 120 words. Tokipona was developed by Canadian Sonia Helen Kisa (Sonya Lang) in 2001.

This language is almost the exact opposite of Ithkuil: it is melodic, there are no cases or complex morphemes, and most importantly, every word in it is very polysemantic. The same construction can mean completely different things. For example, "jan li pona" is " good man” (if we just point to the person) or “the person is fixing” (we point to the plumber).

The same thing in Toki Pona can also be called differently, depending on the attitude of the speaker towards it. Thus, a coffee lover might call it “telo pimaje wawa” (“strong dark liquid”), while a coffee hater might call it “telo ike mute” (“very bad liquid”).

All land mammals are designated by one word - soweli, so a cat can be distinguished from a dog only by directly pointing to the animal.

This ambiguity serves reverse side simplicity of tokipona: words can be learned in a few days, but memorizing already established stable phrases will take much more time. For example, "jan" is a person. “Jan pi ma sama” - compatriot. And “roommate” is “jan pi tomo sama.”

Toki Pona quickly gained fans - the community of fans of this language on Facebook numbers several thousand people. Now there is even a Tokipono-Russian dictionary and grammar of this language.

The Internet allows you to learn almost any artificial language and find like-minded people. But in real life Artificial language courses are almost non-existent. The exception is groups of students studying Esperanto, the most popular international auxiliary language today.

There is also sign language, and if it seems too complicated to someone,

know - there is.

Constructed languages- specialized languages in which vocabulary, phonetics and grammar have been specially developed to implement specific purposes. Exactly focus distinguishes artificial languages from natural ones. Sometimes these languages are called fake, made-up languages. invented language, see example of use in the article). There are already more than a thousand such languages, and new ones are constantly being created.

Nikolai Lobachevsky gave a remarkably clear assessment artificial languages: “To what do science, the glory of modern times, the triumph of the human mind, owe their brilliant successes? Without a doubt, to your artificial language!

The reasons for creating an artificial language are: facilitating human communication (international auxiliary languages, codes), giving fiction additional realism, linguistic experiments, ensuring communication in a fictional world, language games.

Expression "artificial language" sometimes used to mean planned languages and other languages developed for human communication. Sometimes they prefer to call such languages “planned”, since the word “artificial” has a disparaging connotation in some languages.

Outside the Esperantist community, a "planned language" means a set of rules applied to natural language with the purpose of unifying it (standardizing it). In this sense, even natural languages can be artificial in some respects. Prescriptive grammars, described in ancient times for classical languages such as Latin and Sanskrit, are based on the rules of codification of natural languages. Such sets of rules are somewhere between the natural development of a language and its construction through formal description. The term "glossopoeia" refers to the construction of languages for some artistic purpose, and also refers to these languages themselves.

Review

The idea of creating a new language of international communication arose in the 17th-18th centuries as a result of the gradual decrease in the role of Latin in the world. Initially, these were predominantly projects of a rational language, independent of the logical errors of living languages, and based on the logical classification of concepts. Later, projects based on models and materials from living languages appeared. The first such project was the universalglot, published by Jean Pirro in 1868 in Paris. Pirro's project, which anticipated many details of later projects, went unnoticed by the public.

The next international language project was Volapük, created in 1880 by the German linguist I. Schleyer. It caused quite a stir in society.

The most famous artificial language was Esperanto (Ludwik Zamenhof, 1887) - the only artificial language that became widespread and united quite a few supporters of an international language.

The most famous artificial languages are:

- basic english

- Esperanto

- Makaton

- Volapuk

- interlingua

- Latin-blue-flexione

- lingua de planeta

- loglan

- Lojban

- Na'vi

- novial

- occidental

- solresol

- ifkuil

- Klingon language

- Elvish languages

The number of speakers of artificial languages can only be estimated approximately, due to the fact that there is no systematic record of speakers. According to the Ethnologist reference book, there are "200-2000 people who speak Esperanto from birth."

As soon as an artificial language has speakers who are fluent in the language, especially if there are many such speakers, the language begins to develop and, therefore, loses its status as an artificial language. For example, Modern Hebrew was based on Biblical Hebrew rather than created from scratch, and has undergone significant changes since the creation of the State of Israel in 1948. However, linguist Gilad Zuckerman argues that modern Hebrew, which he calls "Israeli", is a Semitic-European hybrid and is based not only on Hebrew, but also on Yiddish and other languages spoken by followers of the religious movement. rebirth. Therefore, Zuckerman favors the translation of the Hebrew Bible into what he calls "Israeli." Esperanto as modern spoken language differs significantly from the original version published in 1887, so modern editions Fundamenta Krestomatio 1903 requires many footnotes on syntactic and lexical differences between early and modern Esperanto.

Proponents of artificial languages have many reasons for using them. The well-known but controversial Sapir-Whorf hypothesis suggests that the structure of language influences the way we think. Thus, a “better” language should enable the person who speaks it to think more clearly and intelligently; this hypothesis was tested by Suzette Hayden Elgin when creating the feminist language Laadan, which appeared in her novel Native Tongue. Manufactured language can also be used to limit thoughts, like Newspeak in George Orwell's novel, or to simplify, like Tokipona. In contrast, some linguists, such as Steven Pinker, argue that the language we speak is “instinct.” Thus, each generation of children invents slang and even grammar. If this is true, then it will not be possible to control the range of human thought through the transformation of language, and concepts such as "freedom" will appear in the form of new words as old ones disappear.

Proponents of artificial languages also believe that a particular language is easier to express and understand concepts in one area, but more difficult in other areas. For example, different computer languages make it easier to write only certain types of programs.

Another reason for using an artificial language may be the telescope rule, which states that it takes less time to first learn a simple artificial language and then a natural language than to learn only a natural language. For example, if someone wants to learn English, then they can start by learning Basic English. Man-made languages such as Esperanto and Interlingua are simpler due to the lack irregular verbs and some grammatical rules. Numerous studies have shown that children who first learned Esperanto and then another language achieved better language proficiency than those who did not first learn Esperanto.

The ISO 639-2 standard contains the code "art" to represent artificial languages. However, some artificial languages have their own ISO 639 codes (for example, "eo" and "epo" for Esperanto, "jbo" for Lojban, "ia" and "ina" for Interlingual, "tlh" for Klingon, and "io" and "ido" for Ido).

Classification

The following types of artificial languages are distinguished:

- Programming languages and computer languages are languages for automatic processing of information using a computer.

- Information languages are languages used in various information processing systems.

- Formalized linguistics are languages intended for symbolic recording of scientific facts and theories of mathematics, logic, chemistry and other sciences.

- International auxiliary languages (planned) - languages created from elements of natural languages and offered as an auxiliary means of interethnic communication.

- Languages of non-existent peoples created for fictional or entertainment purposes, for example: Elvish language, invented by J. Tolkien, Klingon language, invented by Marc Okrand for a science fiction series "Star Trek", a Na'vi language created for the film Avatar.

- There are also languages that were specifically developed to communicate with extraterrestrial intelligence. For example, Linkos.

According to the purpose of creation, artificial languages can be divided into the following groups:

- Philosophical And logical languages- languages that have a clear logical structure of word formation and syntax: Lojban, Tokipona, Ifkuil, Ilaksh.

- Supporting languages- intended for practical communication: Esperanto, Interlingua, Slovio, Slovyanski.

- Artistic or aesthetic languages- created for creative and aesthetic pleasure: Quenya.

- Languages for setting up an experiment, for example, to test the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis (that the language a person speaks limits consciousness, drives it into a certain framework).

According to their structure, artificial language projects can be divided into the following groups:

- A priori languages- based on logical or empirical classifications of concepts: loglan, lojban, rho, solresol, ifkuil, ilaksh.

- A posteriori languages- languages built primarily on the basis of international vocabulary: Interlingua, Occidental

- Mixed languages- words and word formation are partly borrowed from non-artificial languages, partly created on the basis of artificially invented words and word-formation elements: Volapuk, Ido, Esperanto, Neo.

According to the degree of practical use, artificial languages are divided into the following projects:

- Languages that are widely used: Ido, Interlingua, Esperanto. Such languages, like national languages, are called “socialized”; among artificial ones they are combined under the term planned languages.

- Artificial language projects that have a number of supporters, for example, Loglan (and its descendant Lojban), Slovio and others.

- Languages that have a single speaker - the author of the language (for this reason it is more correct to call them “linguistic projects” rather than languages).

Ancient linguistic experiments

The first mentions of artificial language in the period of antiquity appeared, for example, in Plato's Cratylus in Hermogenes' statement that words are not inherently related to what they refer to; what people use " part of your own voice... to the subject" Athenaeus of Naucratis, in the third book of the Deipnosophistae, tells the story of two men: Dionysius of Sicily and Alexarchus. Dionysius from Sicily created such neologisms as menandros"virgin" (from menei"waiting" and andra"husband"), menekrates"pillar" (from menei, “stays in one place” and kratei, "strong"), and ballantion"spear" (from balletai enantion"thrown against someone"). By the way, the usual Greek words for these three are parthenos, stulos And akon. Alexarchus the Great (brother of King Cassander) was the founder of the city of Ouranoupolis. Afinitus recalls a story where Alexarchus “proposed a strange vocabulary, calling the rooster “the crower of the dawn,” the barber “the mortal razor” ... and the herald aputēs[from ēputa, “loud-voiced”]. While the mechanisms of grammar proposed by classical philosophers were developed to explain existing languages (Latin, Greek, Sanskrit), they were not used to create new grammar. Panini, who supposedly lived at the same time as Plato, in his descriptive grammar of Sanskrit created a set of rules to explain the language, so the text of his work can be considered a mixture of natural and artificial language.

Early artificial languages

The earliest artificial languages were considered "supernatural", mystical, or divinely inspired. The Lingua Ignota language, recorded in the 12th century by St. Hildegard of Bingen, became the first completely artificial language. This language is one of the forms of a private mystical language. An example from Middle Eastern culture is the Baleibelen language, invented in the 16th century.

Improving the language

Johannes Trithemius, in his work Steganography, tried to show how all languages can be reduced to one. In the 17th century, interest in magical languages was continued by the Rosicrucian Order and the alchemists (like John Dee and his Enochian language). Jacob Boehme in 1623 spoke of the “natural language” (Natursprache) of the senses.

The musical languages of the Renaissance were associated with mysticism, magic and alchemy and were sometimes also called the language of birds. The Solresol Project of 1817 used the concept of "musical languages" in a more pragmatic context: the words of the language were based on the names of seven musical notes, used in various combinations.

17th and 18th centuries: the emergence of universal languages

In the 17th century, such “universal” or “a priori” languages appeared as:

- A Common Writing(1647) by Francis Lodwick;

- Ekskybalauron(1651) and Logopandecteision(1652) by Thomas Urquhart;

- Ars signorum George Dalgarno, 1661;

- Essay towards a Real Character, and a Philosophical Language John Wilkins, 1668;

These early taxonomic artificial languages were dedicated to creating a system of hierarchical classification of language. Leibniz used a similar idea for his 1678 Generalis language. The authors of these languages were not only busy abbreviating or modeling grammar, but also compiling a hierarchical system of human knowledge, which later led to the French Encyclopedia. Many of the artificial languages of the 17th and 18th centuries were pasigraphic or purely written languages that had no oral form.

Leibniz and the compilers of the Encyclopedia realized that it was impossible to definitely fit all human knowledge into the “Procrustean bed” of a tree diagram, and, therefore, to build an a priori language based on such a classification of concepts. D'Alembert criticized the projects of universal languages of the previous century. Individual authors, usually unaware of the history of the idea, continued to propose taxonomic universal languages until the early 20th century (for example, the language of Rho), but the most recent languages were limited to a specific area, such as mathematical formalism or computing (for example, Linkos and languages programming), others were designed to resolve syntactic ambiguity (eg Loglan and Lojban).

19th and 20th centuries: auxiliary languages

Interest in a posteriori auxiliary languages arose with the creation of the French Encyclopedia. During the 19th century there appeared large number international auxiliary languages; Louis Couture and Leopold Law in their essay Histoire de la langue universelle (1903) examined 38 projects.

The first international language was Volapuk, created by Johann Martin Schleyer in 1879. However, disagreements between Schleyer and some famous users of the language led to a decline in the popularity of Volapük in the mid-1890s, and this gave rise to Esperanto, created in 1887 by Ludwik Zamenhof. Interlingua originated in 1951 when the International Assistive Language Association (IALA) published its Interlingua-English dictionary and accompanying grammar. The success of Esperanto has not prevented the emergence of new auxiliary languages, such as Leslie Jones's Eurolengo, which contains elements of English and Spanish.

The 2010 Robot Interaction Language (ROILA) is the first language for communication between humans and robots. The main ideas of the ROILA language are that it should be easy for humans to learn and effectively recognized by computer speech recognition algorithms.

Artistic languages

Artistic languages created for aesthetic pleasure begin to appear in early modern literature (in Gargantua and Pantagruel, in utopian motifs), but only become known as serious projects at the beginning of the 20th century. A Princess of Mars by Edgar Burroughs was perhaps the first science fiction novel to use artificial language. John Tolkien was the first scholar to discuss artistic languages publicly, giving a lecture entitled "A Secret Vice" at a convention in 1931.

By the beginning of the first decade of the 21st century, artistic languages have become quite common in science fiction and fantasy works, which often use an extremely limited but defined vocabulary, indicating the existence of a full-fledged artificial language. Artistic languages appear, for example, in Star Wars, Star Trek, The Lord of the Rings (Elvish), Stargate, Atlantis: The Lost World, Game of Thrones (Dothraki and Valyrian), Avatar, and the computer adventure games Dune and Myst.

Modern artificial language communities

From the 1970s to the 1990s, various journals about artificial languages were published, for example: Glossopoeic Quarterly, Taboo Jadoo And The Journal of Planned Languages. The artificial languages mailing list (Conlang) was founded in 1991, and later the AUXLANG mailing list dedicated to international auxiliary languages was spun off. In the first half of the 1990s, several journals dedicated to artificial languages were published in the form of emails, several journals were published on websites, we are talking about journals such as: Vortpunoj and Model Languages(Model Languages). Sarah Higley's survey results indicate that members of the artificial language mailing list are primarily men from North America and Western Europe, with fewer participants from Oceania, Asia, the Middle East and South America, the ages of participants range from thirteen to sixty years; the number of women participating increases over time. More recently founded communities include the Zompist Bulletin Board(ZBB; since 2001) and the Conlanger Bulletin Board. On forums there is communication between participants, discussion of natural languages, participants solve questions - do certain artificial languages have the functions of natural language, and which ones? interesting features natural languages can be used in relation to artificial languages; short texts that are interesting from the point of view of translation are posted on these forums, as well as discussions are held about the philosophy of artificial languages and the goals of the participants in these communities. ZBB data showed that a large number of participants spend relatively little time on one artificial language and move from one project to another, spending approx. four months for learning one language.

Collaborative artificial languages

The Thalosian language, the cultural basis for the virtual state known as Thalossa, was created in 1979. However, as interest in the Talosian language grew, the development of guidelines and rules for this language since 1983 was undertaken by the Committee for the Use of the Talosian Language, as well as other independent organizations of enthusiasts. The Villnian language draws on Latin, Greek and Scandinavian. Its syntax and grammar resemble Chinese. The basic elements of this artificial language were created by one author, and its vocabulary was expanded by members of the Internet community.

Most artificial languages are created by one person, like the Talos language. But there are languages that are created by a group of people, for example the Interlingua language, developed International Association auxiliary language and Lojban, created by the Logical Language Group.

Collaborative development of artificial languages has become common in recent years, as artificial language designers began to use Internet tools to coordinate design efforts. NGL/Tokcir was one of the first Internet collaborative designed languages, whose developers used a mailing list to discuss and vote on grammatical and lexical design issues. Later, The Demos IAL Project developed an International Auxiliary Language using similar collaborative methods. The Voksigid and Novial 98 languages were developed through mailing lists, but neither was published in its final form.

Several artistic languages have been developed on various language Wikis, usually with discussion and voting on phonology and grammatical rules. An interesting option language development is a corpus approach, such as Kalusa (mid-2006), where participants simply read a corpus of existing sentences and add their own, perhaps maintaining existing trends or adding new words and constructions. The Kalusa engine allows visitors to rate offers as acceptable or unacceptable. In the corpus approach, there are no explicit references to grammatical rules or explicit definitions of words; the meaning of words is inferred from their use in different sentences of the corpus by different readers and participants, and grammatical rules can be inferred from the sentence structures that were rated most highly by participants and other visitors.

(USA)

Jan van Steenbergen, Igor Polyakov

G. I. Muravkin (Berlin)

Write a review about the article "List of artificial languages"

Notes

Literature

- Histoire de la langue universelle. - Paris: Librairie Hachette et Cie, 1903. - 571 p.

- Drezen E.K. For a universal language. Three centuries of quest. - M.-L.: Gosizdat, 1928. - 271 p.

- Svadost-Istomin Ermar Pavlovich. How will a universal language emerge? - M.: Nauka, 1968. - 288 p.

- Dulichenko A. D. Projects of universal and international languages (Chronological index from the 2nd to the 20th centuries) // Scientific notes of the Tartu State University. un-ta. Vol. 791. - 1988. - pp. 126-162.

Links

| ||||||||||||||||||||

About the company Foreign language courses at Moscow State University

About the company Foreign language courses at Moscow State University Which city and why became the main one in Ancient Mesopotamia?

Which city and why became the main one in Ancient Mesopotamia? Why Bukhsoft Online is better than a regular accounting program!

Why Bukhsoft Online is better than a regular accounting program! Which year is a leap year and how to calculate it

Which year is a leap year and how to calculate it