The most ancient icons of the Christian world

8 189

The earliest prayer icons that have survived to this day date back to the period no earlier than the 6th century. They were made using the encaustic technique (Greek ἐγκαυστική - burning), when paint was mixed on heated wax. It should be noted that all paints consist of paint powder (pigment) and a binding material - oil, egg emulsion or, as in this case, wax.

Encaustic painting was the most widespread painting technique of the ancient world. It was from the ancient Hellenistic culture that this painting came to Christianity.

Encaustic icons are characterized by a certain “realism” in the interpretation of the image. The desire to document reality. This is not just a cult object, it is a kind of “photography” - living evidence of the real existence of Christ, the Virgin Mary, saints and angels. After all, the holy fathers considered the very fact of the true incarnation of Christ to be the justification and meaning of the icon. The invisible God, who has no image, cannot be depicted.

But if Christ was truly incarnate, if His flesh was real, then it was depictable. As Rev. later wrote. John of Damascus: “In ancient times, God, incorporeal and without form, was never depicted. Now that God has appeared in the flesh and lived among men, we portray the visible God.” It is this evidence, a kind of “documentary”, that permeates the first icons. If the Gospel, in the literal sense, good news, is a kind of report about the incarnate Lord, crucified for our sins, then the icon is an illustration of this report. There is nothing surprising here, because the word icon itself - εἰκών - means “image, image, portrait.”

But the icon conveys not only and not so much the physical appearance of the person depicted. As the same reverend writes. John: “Every image is a revelation and demonstration of what is hidden.” And in the first icons, despite the “realism”, the illusory transmission of light and volume, we also see signs of the invisible world. First of all, this is a halo - a disk of light surrounding the head, symbolizing the grace and radiance of the Divine (St. Simeon of Thessalonica). In the same way, symbolic images of disembodied spirits - angels - are depicted on the icons.

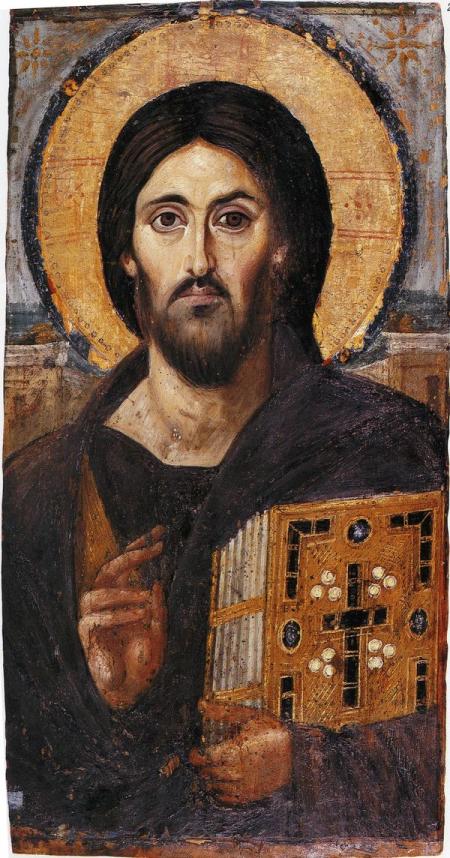

The most famous encaustic icon now can probably be called the image of Christ Pantocrator, kept in the monastery of St. Catherine in Sinai (it is worth noting that the collection of icons of the Sinai monastery is completely unique, the oldest icons have been preserved there, since the monastery, having been outside the Byzantine Empire since the 7th century, suffered from iconoclasm).

The Sinai Christ is painted in the free pictorial manner inherent in Hellenistic portraiture. Hellenism is also characterized by a certain asymmetry of the face, which has already caused a lot of controversy in our time and prompted some to search for hidden meanings. This icon was most likely painted in one of the workshops in Constantinople, as evidenced by the high level of its execution.

Christ Pantocrator. VI century. Monastery of St. Catherine. Sinai

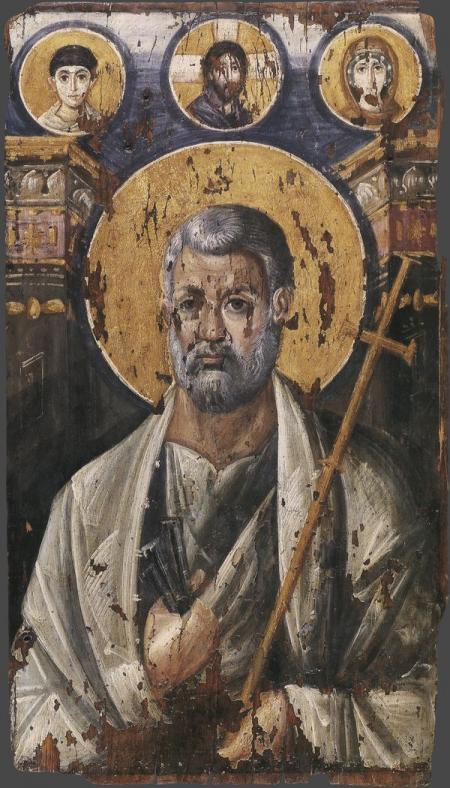

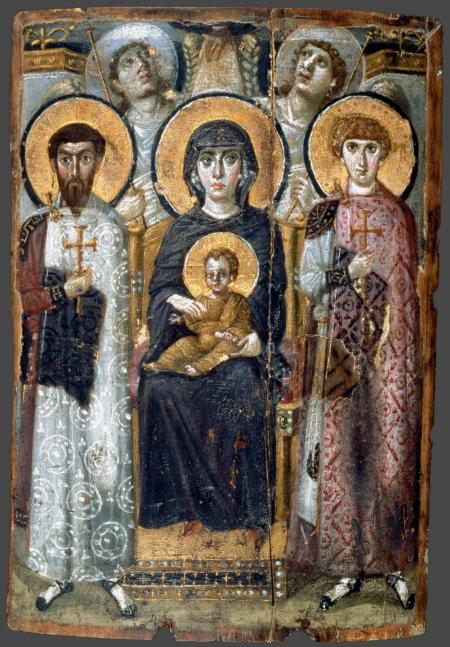

Most likely, the same circle also includes icons of the Apostle Peter and the Mother of God on the throne, accompanied by saints and angels.

Apostle Peter. VI century. Monastery of St. Catherine. Sinai

Theotokos with the upcoming saints Theodore and George. VI century. Monastery of St. Catherine. Sinai

The Virgin Mary is depicted as the Queen of Heaven, seated on a throne, accompanied by saints dressed in court robes and angels. The simultaneous royalty and humility of Mary are interestingly demonstrated: at first glance, she is dressed in a simple dark tunic and maforium, but its dark purple color tells us that this is purple, and purple robes in the Byzantine tradition could only be worn by the Emperor and Empress.

A similar image, but painted later in Rome, represents the Mother of God - without any hints - in full imperial vestments and crown.

Our Lady - Queen of Heaven. Early 8th century. Rome. Basilica of Santa Maria in Trastavere

The icon has a ceremonial character. It follows the style of ceremonial imperial images. At the same time, the faces of the depicted characters are filled with softness and lyricism.

Our Lady - Queen of Heaven. Angel. Fragment

The image of saints in court clothes was supposed to symbolize their glory in the Kingdom of Heaven, and to convey this height, Byzantine masters resorted to forms that were familiar to them and understandable for their time. The image of Saints Sergius and Bacchus, now kept in Kyiv in the Bogdan and Varvara Khanenko Museum of Art, was executed in the same style.

St. Sergius and Bacchus. VI century. Kyiv. Museum of Art. Bogdan and Varvara Khanenko

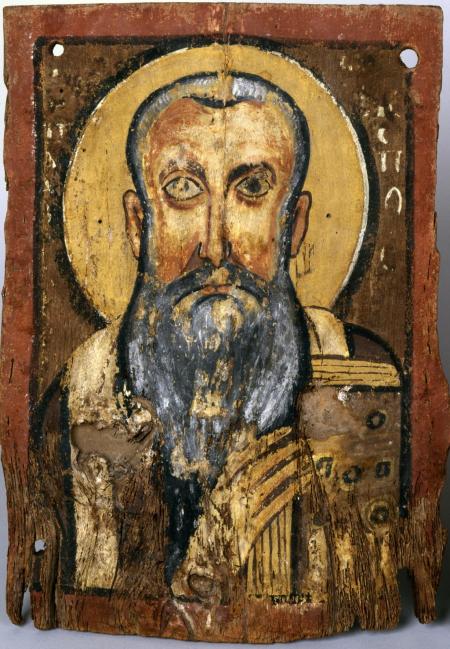

But, in addition to the refined art of the cultural centers of the Empire, early icon painting is also represented by a more ascetic style, which is distinguished by greater sharpness, a violation of the proportions of the depicted characters, and an emphasized size of heads, eyes, and hands.

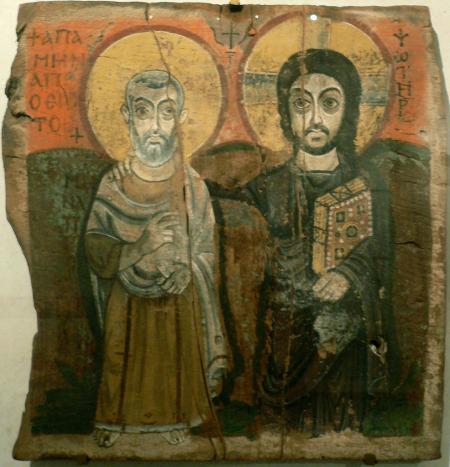

Christ and St. Mina. VI century. Paris. Louvre

Such icons are typical for the monastic environment of the East of the Empire - Egypt, Palestine and Syria. The harsh, sharp expressiveness of these images is explained not only by the level of provincial masters, which is undoubtedly different from the capital, but also by local ethnic traditions and the general ascetic orientation of this style.

Bishop Abraham. VI century. State Museums of Dahlem. Berlin.

Without any doubt, one can be convinced that long before the iconoclastic era and the 7th Ecumenical Council, which condemned iconoclasm, there was a rich and varied tradition of icon painting. And the encaustic icon is only part of this tradition.

Rus' and the Horde - the Great Empire...

Vatican - “the secret always becomes clear”...

Legends and myths about the legendary Avalon...

Nail care

Nail care Prom hairstyle for long hair

Prom hairstyle for long hair 18 wonderful New Year cards that even a child can make

18 wonderful New Year cards that even a child can make The best set of exercises for morning exercises

The best set of exercises for morning exercises